This week, we open a new exhibition in Campinas, north of São Paulo – a historically agricultural region where the history of slavery has left many legacies. And which has a curious connection to the history of photography.

Even though slavery was abolished in Brazil in 1888, the plantation owners of Campinas (then called São Carlos) were the last ones to fully emancipate the enslaved, keeping them under precarious conditions to keep their economic interests in the international coffee market into the early 20th century. At that point, European migration to Brazil was in full swing, resulting in the substitution of Black labor for poor European farmers seeking to make fortune in the New World and the growth of industrialization. This resulted in an effacing of Black history in the region, and in the Black population still fighting for historical reparations.

An important part of the history of photography also played out in this area of rich farmland. In the early 19th century, an inventive French draughtsman with an adventurous spirit – Hercule Florence – settled in the area after spending years on a scientific mission all over Brazil having produced an enormous archive of drawings and prints of fauna, flora and indigenous peoples along with an extensive diary. In late 1820s Campinas, he worked with an apothecary and began to experiment with various ways of fixating images on paper. His experiments with chemicals and exposure durations eventually led him to a successful formula which he called “photography”, learn more here. He did send his invention to be patented in Paris, but due to the fact that Hercule lived in a remote place in the Brazilian hinterlands his application arrived only too late. Daguerre had already won the race, and is now attributed as the inventor of photography.

Florence became a local celebrity of sorts, inventing many other things, but was mostly forgotten until a foundation was created by his kin to resurrect his legacy. For a few years now, there is a yearly photography festival dedicated to him in Campinas – and this year we are participating.

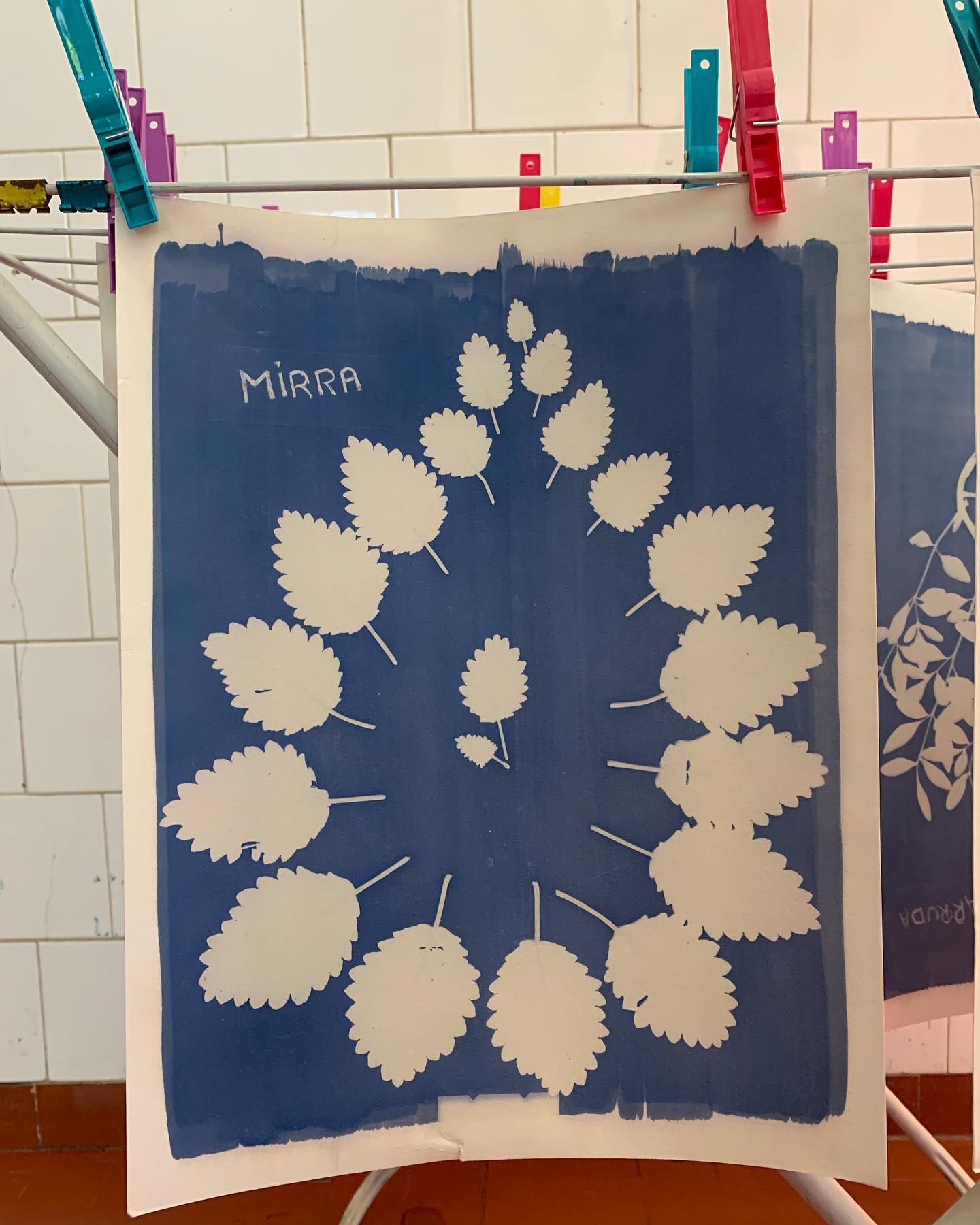

So we combined these two narratives of historical effacement into one. Together with the photography collective Câmera Lúcida (specializing in analogue photographic techniques), and members of the Afro-Brazilian cultural group Fazenda Roseira in Campinas – women, healers, leaders – a herbarium of plants used for medicinal and ritual purposes in Afro-Brazilian religions was created using the photographic technique of the cyanotype – a process of revealing images on emulsified paper with sunlight (invented around the time Florence made his experiments in the early 19th century). The work is called “Ways of Healing (Ancestral Herbarium).

The knowledge of these plants are examples of how knowledge is handed down from generation to generation, and is also a part of a larger discourse for environmental and social justice in Brazil.